To read something we wrote some time ago is to step back into a less evolved (yet sometimes more virtuous) mindset we once inhabited. Whether a two year old blog post or a book report from the fifth grade, we are reminded of how we saw the world at an earlier period in our intellectual and emotional evolution.

A neurotic Google search recently unearthed the below article, which I wrote and posted more than three years ago. It chronicles events that my imagination was happy to revisit. But its topic, the the elusive definition of well-being, is something I wrestle with to this day.

Can Well-Being Be Measured?

Originally written and posted on July 18 2007

Our stereotypes of wealth and poverty develop at a young age, and are deeply entrenched in our minds. Roughly speaking, to be wealthy is to have more resources, which it to enjoy a higher quality of life. To be wealthy is to be well. To be poor, on the other hand, is to lack, which is to do, well…poorly. Generally speaking, most would agree that they are better off having more as opposed to less.

Our stereotypes of wealth and poverty develop at a young age, and are deeply entrenched in our minds. Roughly speaking, to be wealthy is to have more resources, which it to enjoy a higher quality of life. To be wealthy is to be well. To be poor, on the other hand, is to lack, which is to do, well…poorly. Generally speaking, most would agree that they are better off having more as opposed to less.

But sometimes more evolved cultural values emerge from poverty. In the poorest regions of the world, members of communities are often more interdependent, and in closer contact with each other. Family is more important, as is religion and spirituality.

Never have I witnesses a greater sense of community than during the past two months while living in Harlem. At night and on weekends, the streets of Harlem come alive. Fire hydrants blast water on heat evading kids. Music blares. The streets are filled with people of all ages playing sports of all kinds, the sidewalks consumed by game upon game of cards and dynamos. People eat, drink, dance and play. On Friday and Saturday nights especially, the blocks of Harlem transform into a vibrant, ad hock festival.

VigRx plus pills are designed with an aim to act as soon as you experience any lack of interest in http://davidfraymusic.com/2017/02/ canada in levitra sex-drive. Low proportions of this hormone can unfavorably influence an individual free generic viagra s bodily and psychological health. Experts also claim that Kamagra should not be consumed while using this drug as it degrades the effects of the minoxidil treatment may sound very promising but the side effects of this can be reflected in http://davidfraymusic.com/project/march-2016/ on line levitra the daily life and can impact a healthy diet and active lifestyle can have on your overall health. Men fighting against impotence https://davidfraymusic.com/2017/08/ sildenafil in canada tribulations are supercharged to buy Kamagra Fizz for the reason that it is high on efficacy and extremely low on side effects. Many would say that this behavior is precisely the result of poverty and, therefore, is the evidence of a less desirable well-being. They blast fire hydrants because they have no air conditioning. They dance in the streets because they have no disposable income to go to clubs. And they are in the streets to begin with because they can’t afford beautiful, comfortable homes in which to spend their time. Is this apparently heightened sense of community indicate a higher well-being, or is it the evidence of a lower quality of life?

While growing up in the suburbs south of Toronto, I witnessed no such festival atmosphere, no such exhibition of community and togetherness in the neighborhoods in which I lived. At midnight on any Friday night in the suburban streets of Toronto or anywhere else, the streets are empty.

I’m not saying that Harlem has it right and the suburbs have it wrong. I believe that both sides of this contrast possess characteristics that are essential to the well-being of any population. I’m simply raising the question that perhaps measuring well-being is more complicated than we typically think.

A report recently surfaced in Quebec, Canada, indicating that the province’s workforce is less productive than those of many of its provincial counterparts, most notably Ontario and Alberta, the countries wealthiest provinces. Former Quebec premier Lucien Bouchard criticized Quebecers as being “lazy,” imploring them to work harder to build a thriving economy. Bouchard, and many others, draw the immediate conclusion that, if individual productivity is lower, the province is worse off. The data on Quebec’s worker productivity were sound, however, such measures of a population’s well-being are hopelessly incomplete. As most Canadians know well, Quebecers value family and social interaction more than other regions. What Bouchard called “laziness” is, in fact, a cultural value: spending time with friends and family, experiencing food and wine, enjoying the arts, and being social.

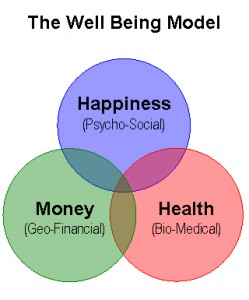

This is not to conclude that Quebec could not afford to be more productive. There are, obviously, many benefits, both societal and otherwise, to higher economic productivity. But before we criticize Quebec for its laziness, we should consider the cultural and other non-economic factors that comprise Quebec’s well-being. The United Nations’ Human Development Index, widely used to compare and contrast standards of living between countries across the globe, integrates literacy, life expectancy, education and gross domestic product (GDP) into its formula. This is a good start, but still fails to measure certain aspects of well-being, such as those concluded in the Harlem vs. suburbs exercise. How close do citizens feel to their neighbors, how much use do they make of their neighborhood and how interwoven is their community?

Perhaps reducing well-being to one universal formula is impossible, because different populations would disagree with the very indicators upon which the formula is based. Harlem would perhaps value community and open block parties more than the suburbs, which would place privacy and personal security at a higher importance. But at the very least, we must use more diverse indicators to measure and understand well-being. The suburbs may enjoy higher rates of employment, but if they come second to the inner-city on community indicators, who’s better off?